Residents Can Track 2018 Flood Bond Projects on New Dashboard

The Harris County Commissioners Court held a public hearing on its controversial budget and tax rate on Thursday, but another agenda item was top of mind for Billy Guevara, Doris Brown, and members of the disaster response advocacy group West Street Recovery: the unveiling of a dashboard to track $2.5 billion worth of flood bond projects that were approved seven years ago.

Guevara lost six family members who tried to outrun Hurricane Harvey in 2017 and drowned in the floodwaters of Halls Bayou. Brown’s northeast Houston home flooded, the roof caved in, and FEMA rejected her application for assistance. West Street Recovery was formed shortly after Harvey to help Houstonians like Guevara and Brown.

Hurricane Harvey devastated Houston and southeast Texas, flooding more than 100,000 structures and causing $125 billion in damage. At least 100 people died.

Harris County responded by putting a multibillion-dollar bond issue before voters in 2018. The measure passed with 86 percent casting ballots in favor, and local leaders got to work submitting projects.

But until this week, there was no way for a member of the public, or even an elected county commissioner, to get a simple snapshot on the Harris County Flood Control District website of what’s been accomplished and what’s in the pipeline.

Precinct 1 Commissioner Rodney Ellis, the only current official who was seated at the time of the bond program, has demanded that the county follow an equity framework that prioritizes flood mitigation projects in historically underserved areas that need it most.

Commissioner Tom Ramsey has argued that Ellis’ definition of equity puts the projects in Precinct 1 at the top of the priority list, neglecting much-needed flood mitigation in other areas of the county.

During a Commissioners Court meeting in June, Harris County Flood Control District Director Tina Petersen heard from an irate crowd, including Guevara and Brown, who said they were promised that flood mitigation projects would be initiated in their neighborhoods to prevent “another Harvey.” They voted for the bonds and supported the framework that was supposed to address “the worst first.”

They didn’t know if the projects in their neighborhoods were funded and slated for construction or if they’d been discarded because they were found not to be feasible. Residents and commissioners accused the flood control district of not being transparent.

“We could land a guy on the moon easier than what we’re trying to do here, in terms of how complicated we’ve made it,” Ramsey said at the June meeting. “It shouldn’t be this hard to figure out whether a project is going to be done in your neighborhood or not. I have to send a registered professional engineer with 20 years of experience to go meet for two hours to try to figure out what projects are being done, just in my precinct.”

Many suggested a streamlined “one-stop shop” where residents and commissioners could track projects and hold officials accountable to do what they said they’d do when the bond passed.

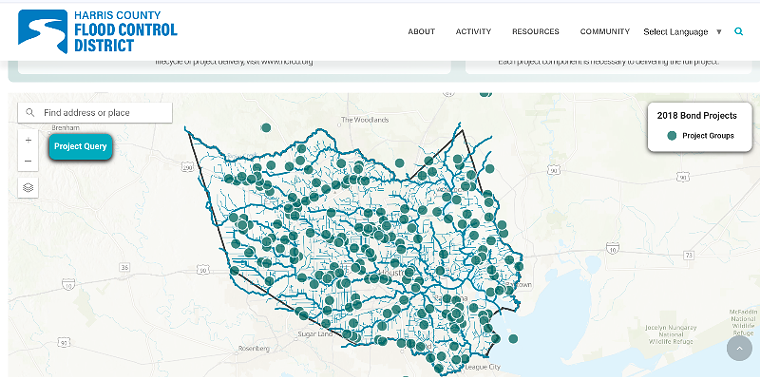

Petersen and her team heard the mandate, and the Harris County Flood Control District rolled out a dashboard this week that displays more than 100 projects with detailed information about the scope, benefits, completion status, and funding sources for each. Residents can type in their address for a micro view of projects near their neighborhoods.

A dashboard unveiled this week allows residents to track projects approved in a 2018 bond.

Screenshot

Flood Control District Chief External Affairs Officer Emily Woodell met with the media prior to Thursday’s court meeting to review the dashboard. In addition to providing the public display of all things related to the 2018 flood bond package, Woodell said her team has been meeting every Friday morning since July with staffers from each of the four county commission precinct offices.

“There’s been a massive amount of effort to really, literally, all come to the table with a shared understanding of the program and a shared understanding of benefits to make sure we’re moving this forward in a responsible way,” she said.

A dashboard doesn’t fix Harris County’s infrastructure but it does provide much-needed transparency, Woodell added. Rumors abounded earlier this year that the bond program faced a massive deficit due to inflation. It’s important for the voters to see not just which projects are getting done, but how they’re being funded, she said.

Voters approved a $2.5 billion bond but the needs assessment at that time amounted to more than $5 billion. Flood control district officials have leveraged the bond funds into an additional $2.7 million in partnership funding, representing a 109 percent return on investment, Woodell explained. If a project doesn’t have funding or the necessary cooperation of a government entity, it’s being paused.

Currently about 24 projects are paused, and “solid engineering estimates” show the amount needed to fund them is $408 million, Woodell said.

“We think it’s really important and frankly this is something we’ve been wanting to spend time on for a long time,” she said of the dashboard. “What we’re focused on doing is providing the data in a lot of different ways. When you talk about $5.2 billion, you lose the sense of scale and you lose the sense of what’s going on. We’re focused on making sure that when we talk funding, we’re talking spent funds, committed funds, and then total funds so that people know where their tax dollars are going.”

“We’re also getting into where the projects are in the overall delivery process,” she added. “How is my watershed’s funding stacking up to other people’s funding?”

Based on any potential directives given at Thursday’s Commissioners Court meeting, which was still underway at press time, the dashboard will be updated early next week to reflect new priorities and funding allocations, Woodell said.

A lot of work has been done since the program was initiated, but some of it — such as design work and right-of-way acquisition — isn’t immediately visible while driving through Houston neighborhoods.

The new dashboard shows 181 approved “bond IDs,” categories such as Greens Bayou Watershed, Buffalo Bayou Watershed, and Galveston Bay Watershed. Within those bond IDs are about 400 projects. About half of those projects are finished, Woodell said.

“One of the things that we’ve gotten away from, just to be totally honest with you, is that this really was in response to Harvey,” she said. “It was seven years ago but it feels like it was yesterday. The damage was countywide. I think one of the things that’s been lost in this is just how much work has been done already and the benefits that are on the ground right now. We know that tens of thousands of people are safer.”

Each of the 2018 bond projects has its own page on the dashboard that details the construction timeline and associated costs.

Screenshot

One of the big wins for the bond program, according to Woodell, was the construction of more than 16,000 acre-feet of stormwater detention.

“That’s like if you took Minute Maid Park and stacked it 1,000 feet with stormwater,” she said. “It’s an amazing amount of capacity we’ve been able to add across the county. We’ve also constructed miles and miles of channel conveyance improvements. What that looks like is making sure our channels can actually move water and they have more capacity.”

As new commissioners were elected and Petersen was appointed executive director in 2022, the bond program remained “highly conceptual,” Woodell said.

“There were not a lot of hard projects included in the bond program,” she said. “There was a ton of engineering and analysis that was needed to be able to refine those concepts and actually build projects. The back-of-the-napkin things had to be turned into things that could be built, and there’s a lot of work that goes into that.”

A prioritization framework was adopted by Commissioners Court in 2019 and later updated by the Harris County Community Flood Resilience Task Force in 2022.

The flood control district, which reports to Commissioners Court, has followed the framework throughout the process, according to Petersen and Woodell, but Commissioner Ellis said this week he intends to hold them accountable to ensure vulnerable neighborhoods are being prioritized.

Ellis said he was pleased with the action taken in June to secure $262.5 million for urgent needs, including $118 million for Greens Bayou.

“I will continue to push for full implementation of the flood equity framework; no cuts to feasible projects in underserved areas; transparent reporting on project status, funding, and timelines; and deployment of all remaining flood bond funds according to equity principles,” Ellis said in an email. “We cannot back off. Equity isn’t a slogan. It’s a promise.”

Some projects have been paused or eliminated from the to-do list because they were found to be “unfeasible,” Woodell said, meaning there is no engineering solution to move a project forward or a partner hasn’t come to the table. The dollars earmarked to those projects will be shifted to other efforts, Woodell said.

Partnerships with private funders have proved lucrative, however, although the partners get to pick the projects they want to fund and their priorities may not line up with residents who voted for the bond.

“The thing that will slow an infrastructure project down the fastest is uncertainty, whether it’s uncertainty about funding or scope,” Woodell said. “As we’ve refined the program over time, we’ve gotten more and more clarity.”

Doris Brown asks for transparency and accountability at a September 18 meeting of Harris County Commissioners Court.

Screenshot

Public comment was held prior to the dashboard unveiling at Thursday’s Commissioners Court meeting, and while it was clear that several residents had already viewed the one-stop shop, many weren’t satisfied that it addressed their concerns about prioritizing projects in Harris County’s historically underserved neighborhoods.

Community activist Shirley Ronquillo said she volunteered on the Flood Resilience Task Force from 2022 to 2024, but project prioritization based on equity wasn’t discussed.

“I am here on behalf of communities that have been historically neglected and left to flood time and time again,” she said. “I applied for the task force under the illusion that the community could work alongside Harris County Flood Control and serve as an adviser to equitable flood mitigation solutions. However, my free time, after work, time away from my aging parents, was spent listening to county departments rather than serving as an adviser on projects.”

Doris Brown, the northeast Houston resident whose home flooded during Harvey, also addressed equity.

“Equity means that we must assist people in communities so that everyone ends up with an equal opportunity to thrive,” she said. “It means that communities that have been neglected, if not outright discriminated against, should get investment. All communities deserve to be protected from flooding.”

“For too long, flood control decisions were made on basic cost-benefit analysis that valued a million-dollar home as more important than six $150,000 homes,” she added. “The prioritization matrix that flood control was instructed to use in 2019 and 2022 was supposed to address this, but time and time again, we have seen that flood control does not. It is a betrayal of trust that flood control decided that some projects didn’t need to be passed through the matrix.”

Reign Bowers is an outdoor enthusiast, adventure seeker, and storyteller passionate about exploring nature’s wonders. As the creator of SuperheroineLinks.com, Reign shares inspiring stories, practical tips, and expert insights to empower others—especially women—to embrace the great outdoors with confidence.

Post Comment